How to choose your next legal innovation project: tips from the experts

Kate Fazio, Sara Rayment, Lyria Bennett Moses and Stephanie Abbott are leaders in the legal innovation field. They share some key lessons learned.

Now more than ever, with tools like Josef, lawyers have the ability to change the way they work. But, they still have to decide what to do with those tools

We spoke with some of Australia’s best designers, academics, innovators and consultants in this field to find out how they decide what their next legal innovation project is, and how law firms and legal organisations can make the right decision too.

Minimise input, maximise output

Kate Fazio, Head of Innovation and Engagement, Justice Connect

Justice Connect is arguably Australia’s most innovative and modern community legal centre, with initiatives such as the Gateway Project, which launched earlier this year with funding from Google. The person spearheading it all is Kate Fazio, their Head of Innovation and Engagement. Josef asked her how she and her team choose the areas in their practice that require innovation.

Kate’s focus is all about return on investment. She says that you have to “step right back and start at the beginning.” Look at all of the different processes, products and services in your organisation, and figure out the pain points for staff, clients and other stakeholders. When deciding where to start, ask yourself: “Where can we make improvements that will have the biggest return on investment?”

In doing this ROI analysis, there are two main factors. The first is outcomes. For Kate, in the legal assistance sector, the question is: “How many more people will we be able to help if we do this?” In the commercial world, this question will be more centred around increasing revenue and efficiency, or: “How much money will this make/save us?”

The second factor is about effort. Kate warns against focusing only on “low-hanging fruit”. She also suggests that, once you have identified a problem that needs solving, you should do some research and see whether someone else has already solved it, or a part of it. Not only will this give you ideas on how you too could solve it, but it could give you the tools to do so more easily and efficiently than you may have first assumed. “If something can be automated, it is probably something someone else thought about before and you can probably buy a product to help you with it,” she says.

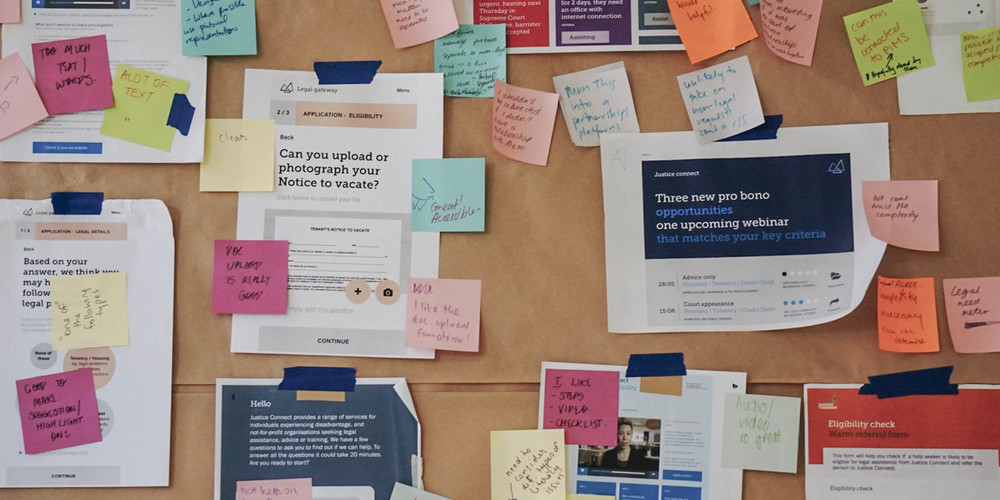

The design process that Justice Connect went through to create their Gateway Project.

Create real value

Sara Rayment, Inkling Legal Design, Founder

Sara is the founder of Inkling Legal Design, a consultancy which helps law firms reimagine legal services. Sara’s legal design credentials are second to none. She studied design-thinking at Stanford University and her experience includes assisting with the design of an online dispute resolution platform for the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law.

For Sara, one of the most important factors in choosing and designing a legal innovation project is value. “Lawyers struggle most with revenue models,” she says. “How will this make money? How will this improve profitability? And how will it fit within their existing services?” These questions are particularly pertinent in an industry that still uses billable hours. If a legal innovation project is going to increase efficiencies, how is a law firm that bills by the hour going to make money from it?

To help lawyers answer these questions, Sara engages in business design with her clients. She looks at the types of clients the law firm has, the revenue models they want to work with and how the project fits into their current workflows.

Part of this analysis also involves considering how the project will increase the competitive advantage of a firm. “Most lawyers lead with price as a way of competing because legal services can be difficult to determine the value of,” she says. “But there are so many other ways of creating competitive advantage that lawyers tend not to be aware of. Accessibility and convenience, for example. Rather than receiving 50 emails about a matter, a well-integrated piece of technology can almost remove that entire workflow from people’s inboxes.” With a well chosen legal innovation project, Sara has seen first hand that “firms can become more profitable, with happier clients and happier lawyers.”

“Ask yourself: What do you actually need? Is this tool actually meeting that need? Or is it doing something else?”

Pick the right technology

Associate Professor Lyria Bennett Moses, Allens Hub for Technology, Law and Innovation, UNSW

Lyria is in the unusual position of combining an academic understanding of law and technology – as Director of the Allens Hub for Technology, Law and Innovation – with hands on experience – as lecturer of the Designing Technology Solutions for Access to Justice course (sponsored by Gilbert + Tobin).

Lyria’s advice to anyone starting a legal innovation project is to choose the right technology. “Really understand what the tech is doing and whether it will actually solve your problem,” she says. “Not everything is a good idea.” For Lyria, these projects often go wrong when people use the wrong tools to solve a problem.

An example is many of the applications of machine-learning tools in the law. Machine-learning tools simply try to predict something from historical data. Therefore, these tools are only useful if the goal is prediction and if the historic data should be projected into the future (particularly given known biases in that data). But, when viewed in this way, many applications of machine-learning in the legal industry begin to look a little odd.

For Lyria, the people running these projects should have first stopped and asked: “Is this what we really want? What is the actual benefit of using historical decisions to determine outcomes for a particular category of disputes, for example?” Because such questions are rarely asked, there are now a number of unintended consequences in the results, including that historical biases are being reproduced into the future. This has been particularly apparent in the use of risk assessment tools in the criminal justice system in the US.

What is some practical advice Lyria would give to a law firm looking to avoid this issue? “Ask yourself: What do you actually need? Is this tool actually meeting that need? Or is it doing something else?”

Choose projects that deliver satisfaction

Stephanie Abbott, Director of Janders Dean

Steph is a Director of Janders Dean, a global consultancy that helps law firms around the world improve their processes and prepare themselves for the future of legal work. An ex-lawyer, Steph has a change and organisational development bent, and a track record in large scale knowledge management and technology projects.

For Steph, the choice is all about payoff. It’s important to see a difference. You should look at three things, she says: “volume/speed, financial impact and emotional payoff”. But, she warns, that doesn’t mean you should tackle the big issues first. “Firms are often tempted to go for the biggest, shiniest project,” she says. “But quite often they seriously underestimate the time, effort and cost and nothing gets done.”

Instead, Steph encourages her clients to start with something that is self-contained and manageable. In this way, they will see results sooner and start building up their “change fitness” for future projects. In part, this is important for emotional reasons. “When you start a diet, you want to see results quickly” Steph says. Tangible outcomes encourage people to keep going, even if it is difficult. In the same way, it is important to see outcomes quickly from early legal innovation projects. After a generally positive experience, firms might be ready to tackle the bigger, harder things.

Steph also thinks that law firms need to remember the emotional side of motivation “We downplay the role of emotions in change processes,” she says. “People change things because they want to, so there needs to be an emotional payoff. There needs to be that sense of accomplishment, satisfaction – making a difference.”